![Athlete with Relay Baton]()

By Tony Holler

Editors Note: Coach Holler will be one of the speakers at the upcoming Track-Football Activation Consortium December 11-12, 2015.

My father Don finally retired after attending 73 first days of school. He turns 80 this December. I have taught for 35 years. So has my wife, Jill. My father-in-law, Ben Brinkley, taught 20 years and then went to work for IEA/NEA in the 70s, helping teachers negotiate contracts. Both my sisters, Nancy Hurckes and Jane Johnston, are career educators. My son, Alec, is a teacher and recently married a teacher. My youngest son, Quinn, plans to teach.

Whew.

We are also a family of coaches. My father, my son, and I have collectively logged 90 years of coaching. I’ve often argued that teaching and coaching are one and the same, but maybe not.

I’m at the age when people seem interested in my opinions. The status quo routinely dismisses the ideas of young people. The wisdom of the elderly sadly goes ignored in the digital age. It seems I am living in a brief window of relevance. Therefore, I write.

As a young teacher in the 1980s, I said, “If our superintendent was a football coach, he would go 0–9 every year.” So I guess this article has been 30 years in the making.

Schools try to be everything to everybody. On the other hand, they mandate a rigid college-bound curriculum. Yet they are at the mercy of elected school boards and politicians. Putting it kindly, elected people are seldom experts in education.

Rehearsed politicians remind me of school superintendents. While Donald Trump may be a clown, he reminds me of a nutty coach and I love it when he boldly proclaims, “We need victories in this country! We don’t have victories anymore!” Victories are elusive in today’s schools.

I’m not involved in school improvement. I serve on no committees. My principal is a good guy, but I’m not on his administrative team. I don’t think the Unit 202 superintendent knows my name. I try to do my job and keep my opinions to myself. As 1960s icon Hunter S. Thompson said, “I have a theory that the truth is never told during the nine-to-five hours.”

I’ve spent most of my life dreaming of better schools. If I were king, high schools would operate like football teams or track programs. Coaches know victory.

![One]()

Sports Are Not Graduation Requirements

No sport is “required” to graduate. Participating in cross country may result in life-long physical fitness, but cross country is not required for graduation. Playing football may improve physical and mental toughness, but football is not compulsory. Basketball might teach teamwork better than anything else in modern schools, but it remains an elective. The world’s greatest sport, track & field, would be ruined if it was mandated.

When you push teenagers, they push back.

Several years ago, I met with our head football coach and proposed a winter speed and strength program. He would be in charge of the weight room, and I would oversee sprint training. I showed him a DVD of athletes doing my workouts. He loved it. He said, “We will make the program mandatory!” I said no. I told him we would make the program so good that kids would want to attend. He agreed. “But if they don’t come, we will make it mandatory!” he added.

Welcome to the world of today’s high schools: required courses, mandatory attendance, and consequences to anyone who resists.

My high school is basically a college prep school. Our main quantifier of success is the ACT Test. Who came up with this idea? The ACT is a predictor of college success—not a quantifier of learning, not an achievement test. If high schools were honest, the mission statement at most of them would be, “To prepare students for the next level.” Before 1970, less than 20% of high school students attended college. Now 65.9% attend college, the majority taking watered-down courses. Some graduate with $100K of debt, a meaningless degree, and an alcohol problem. Educators buy into the madness. Who speaks the truth in education today? Teachers do their job and keep their opinions to themselves. When told to jump, administrators ask “How high?” Colleges collect their profits. College graduates reside in their parents’ basements.

“But if you don’t make math and science mandatory, kids won’t take math and science,” I often hear. I disagree. Improve or eliminate bad courses. Find teachers who relate to kids. Football is brutal. Wrestling is miserable. Cross country athletes run thousands of miles. Despite the blood, sweat, and tears of interscholastic sports, kids keep signing up. So why must we mandate math and science?

“But don’t kids choose their classes in high school?” This is a misconception. Students choose between Honors English and English, but they still must take English.

It seems every kid at my high school takes science, math, English, P.E., history, and a foreign language. They gulp down a cafeteria lunch in 25 minutes and spend 25 minutes warehoused in a study hall. Yet few of them learn. You see, education has become a game of hoop-jumping, meeting arbitrary standards, and taking nonsensical standardized tests. Most high school kids can’t speak a foreign language, but they pass all the tests. They take P.E. but don’t become physically fit. Study guides provide the answers for upcoming tests. Our kids purchase Cliff Notes rather than actually reading The Grapes of Wrath. Worst of all, our kids cheat. Wait. Maybe cheating is not the worst thing. The worst thing is the fact that kids don’t love to read, they don’t get excited about science, and they don’t understand the importance of math. To the average teenager, school sucks.

![Nick Wolf Shot Put]()

Nick Wolf was Plainfield North’s Athlete of the Year in 2015. At 6-3 and 325 pounds, Nick was a star football player, a state qualifier in wrestling, and our best shot putter. If successful completion of soccer, basketball, and baseball were graduation requirements, Nick may not have graduated.

We need to stop pounding square pegs into round holes. If our country prides itself in freedom, why do we incarcerate teenagers?

“Incarceration” is not an overstatement. We have cameras everywhere in our building because schools received millions for security systems after Columbine. From 7:05 to 2:10, our 2,000 students are behind walls. Once in a while, K9 units search for pot. Going home for lunch is forbidden. I joke that high school is “teenage daycare,” but my students don’t laugh.

If schools were more like sports, maybe kids would love school.

Ahh, now we are getting somewhere. If students attended courses by choice, courses would be like sports. Teachers would act more like coaches. Students would not sleep through class. But what if some courses became obsolete? Easy answer. Find a new teacher. Or get rid of the miserable course and create another one worth taking. None of this goes on in today’s schools. The status quo has it all wrapped down tight. The buses run on time; the cafeteria runs like a machine, and students are herded from class to class with amazing efficiency. But our main mission goes unfulfilled.

Let’s flip this idea. What if sports were run like schools? What if they were compulsory? What if we forced every kid to choose a fall sport, a winter sport, and a spring sport? One thing is for sure—I would no longer coach. My athletes motivate me. Their enthusiasm excites me. Everything would turn to shit if kids were forced to play football or run track. The unmotivated, I-don’t-want-to-be-here kids would infect the motivated, inspired ones. Coaches would lose their passion. Coaches would spend their time fulfilling someone else’s agenda—the required material. Coaches would be forced to drink Common Core Kool-Aid and pretend that all is good. Sports would become just like algebra, biology, or Spanish.

![Two]()

Coaches Don’t Spend 80% of Their Time with the 20% of Kids Who Can’t Do the Work

George W. Bush won’t be happy with me. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) had good intentions but is a total disaster. Coaches knew it right away. Coaches don’t pretend to provide the same experience for every kid. Do a wide receiver and an offensive tackle have the same experience? Does the backup quarterback take the same number of snaps as the starter? Does everyone on a basketball team play the same number of minutes and score the same number of points? Do we expect every athlete in a track meet to meet an arbitrary minimum performance standard? Hell no! In point of fact, some kids don’t even make the team. Some kids are left behind and that’s okay.

Education leaders pretend every kid should score touchdowns and classroom teachers should be held accountable. Doing their duty, teachers spend 80% of their time with the 20% of their students lacking the skills to learn what the curriculum mandates. In the meantime, the best students are bored, and their curiosity stagnates.

I will never forget the day our assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction informed over 50 district science teachers that chemistry and physics would become graduation requirements for every Plainfield student. “The data shows that students who take chemistry and physics outperform those that don’t on the ACT,” he assured us. We knew that only the upper half of high school students took chemistry, and even fewer took physics. They naturally performed well on the ACT. But the man in the suit and tie brooked no debate. “You can’t argue with the data,” he told us. He moved on to a higher paying job shortly after changing our graduation requirements. We now water down chemistry and physics courses and pretend. Coaches don’t pretend.

Before you deluge me with hate mail, I am not an elitist. Kids who don’t like football can run cross country. If a kid can’t shoot a basketball, he can wrestle. If a kid can’t hit a baseball, he can run track. I wish we had the same options for students. We used to.

The main solution to this crisis is to stop pretending. Coaches don’t pretend. How has education gone so wrong? When did we decide every kid must be successful in chemistry and physics?

Who is the man behind the curtain? Who is in charge of educational mandates? Why must we obey these mandates? In our attempt to create assertive, independent, and strong-willed adults, we teach kids to be passive, pliable, and obedient. We celebrate our freedom but incarcerate our kids and give them false choices.

![Three]()

Coaches Aren’t Told How to Coach

Every football program in America is unique. The combinations of formations, plays, and defensive schemes are infinite. No two programs are alike. Coaches are free to experiment and innovate. No football coach is told to run the spread offense. No coach is instructed to work on the passing game equally with the running game. Instead, they are encouraged to develop a system that best fits the talents of their team. Why aren’t teachers free to experiment and innovate?

Our varsity team runs the spread offense. My freshman team runs out of the T-formation. The varsity head coach allows me artistic freedom because I teach kids to block and tackle. We don’t make mistakes, and we’ve won 36 consecutive games. Football is football.

I train sprinters much different than the legendary Clyde Hart of Baylor. Coach Hart is in the USATF Hall of Fame. I’m in the ITCCCA Hall of Fame. Track coaches are free to innovate and be creative. Their training methods can be judged by quantifiable results. Sometimes diametrically opposed training systems produce similar results. If I were told to coach my sprinters like Clyde Hart, I would quit.

The best coaches are artists who never stagnate. Coaches are excited to Learning and trying out new things excites them. My best teachers were artists. Teachers are now told to paint by number: “If it’s not on the test don’t teach it.” Really?

One of my favorite Twitter accounts, @Sisyphus38, recently tweeted, “Realize that right now we measure that which is not worth learning, simply because it is easily measured.”

Standardization removes creativity. Teachers don’t have the enthusiasm of coaches because they fulfill someone else’s agenda. They are pawns in someone else’s game. Coaches aren’t.

![Four]()

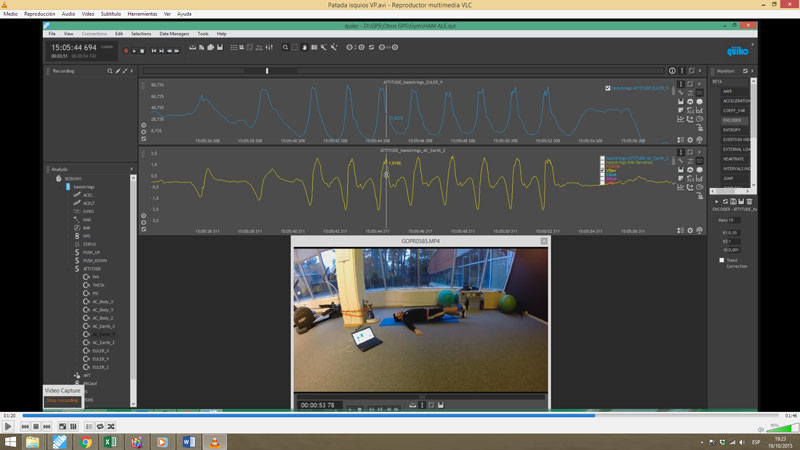

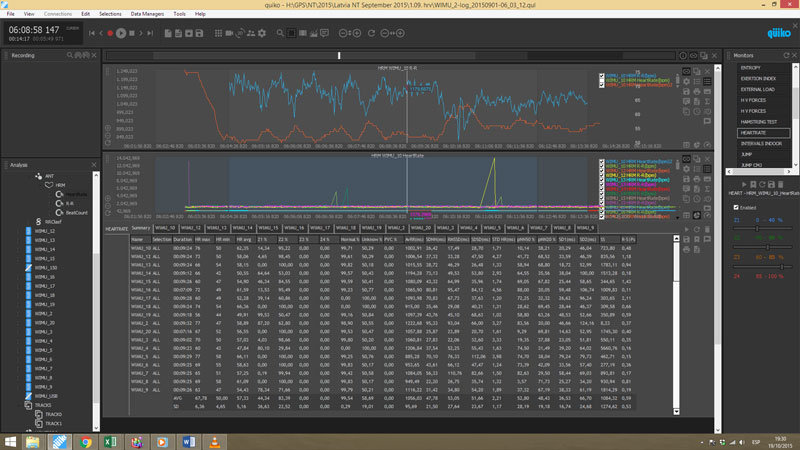

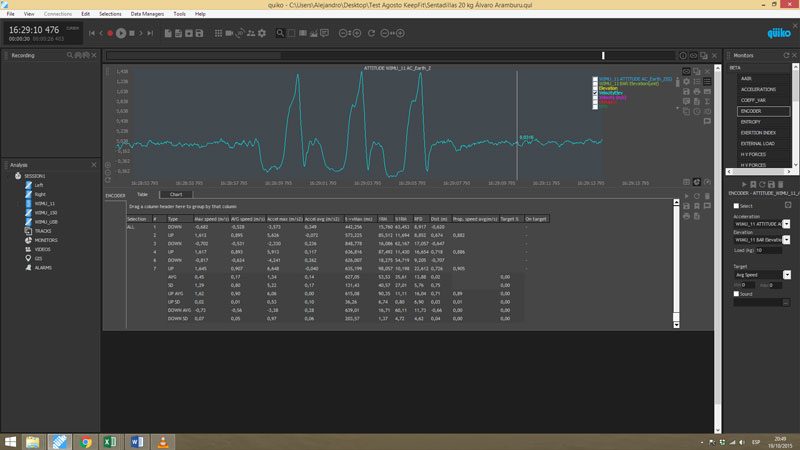

Sports Programs Are Promoted

My track program is so popular that I try to cut my team down to 100 athletes after three weeks of tryouts. My Twitter account, @pntrack, is a terrific PR machine. My website, pntrack.com makes track look fun. My article last year, 10 Reasons to Join the Track Team, went viral. If I did not promote track, I would be lucky to have 30 kids.

![Ohio State Recruits]()

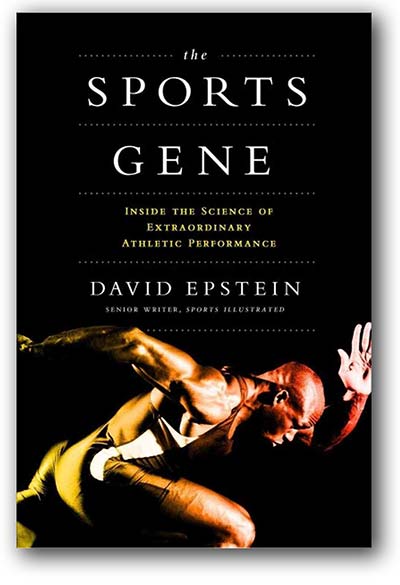

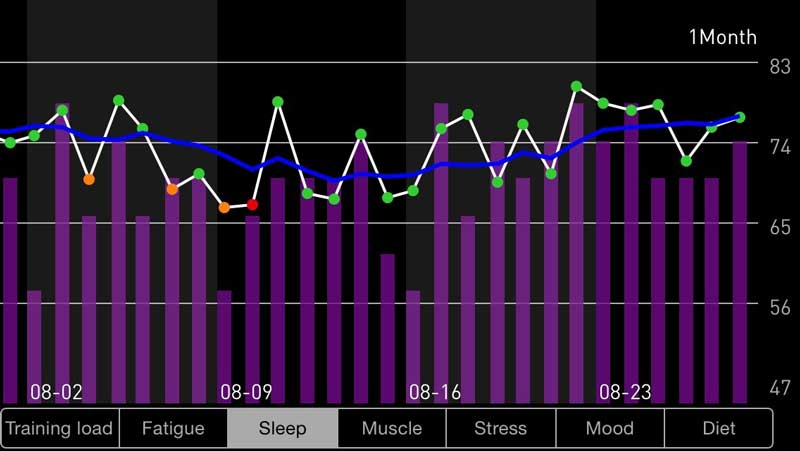

Check out the graph above. Last year I heard that my best sophomore thrower, Arinze Ekowa, wanted to drop track and focus on football. Luckily, he sat in the front row of my chemistry class. I drew this graph right after Ohio State won the national championship to convince him that specialization was not a good idea. #WWUS stands for “What Would Urban Say.” I took a picture of my graph and tweeted it. “The Graph,” as it became known, went viral. Some people hijacked it and got thousands of retweets. One guy used it as the subject of a blog that received over one million shares. It’s been the subject of at least 15 published articles. By the way, Arinze set our sophomore discus record last spring, throwing 153-8. He is presently a dominant defensive lineman. What’s the point? Coaches promote, recruit, and inspire kids to become athletes. Why not promote, recruit, and inspire kids to take physics?

Every year my freshman football team has 60-some guys. Some of our opponents have just half as many. We promote with Twitter: @pnfreshmenFB. We write up every game online. Once games start, we practice only three times a week. We don’t run sprints at the end of practice. Our players spread the word that freshman football at Plainfield North is awesome.

Does geometry promote itself? Does U.S. History have a twitter account? Do students spread the word that Spanish is a terrific course? No. Students are forced to go to school and classes are required. See the problem?

![Five]()

You Play to Win the Game

Coaches are held accountable. Winning is important, very important. Most losing coaches see the writing on the wall and find other pursuits.

Great coaches survive losing seasons because they create a team culture that transcends winning and losing. My track team hasn’t won our conference for seven consecutive years, but you wouldn’t know that by watching our practices. We practice like champions. We compete like champions. Quitting the team is so rare, it seems like it never happens. No one is late for the bus. Enthusiasm for track at Plainfield North is as high as any high school I know. Every fast kid in our school who doesn’t play baseball runs track. Not winning our conference championship last spring does not mean we didn’t have a successful season. Our sprint relays finished 5th and 3rd at the IHSA state meet (42.07 and 1:27.05).

Teachers are also held accountable. This year our science department was told to give students an alternate version of the semester exam on the fifth day of school. The average score in my five honors chemistry classes was 39%. In December, my students will take the actual semester exam. Analyzing improvement of their scores will measure “growth.” The state of Illinois has determined that 25% of our teacher evaluation will be determined by such “growth.” I was glad to see that Seattle teachers had a successful strike to remove test scores from teacher evaluation.

This is why teaching and coaching will never be the same. We pretend that a computer-graded multiple choice test will measure learning just like a stopwatch measures speed. This is 100% bullshit. You would understand if you saw the standardized tests we use to measure learning.

I’m not dismissing the idea of taking tests. I wish all high school students took a comprehensive chemistry achievement test at the end of the year. Such a test could serve as a measure of how students, teachers, and schools stack up with others across the U.S.

However, any and all types of tests should be taken with a grain of salt. Should the conference track meet be the primary evaluator of a high school track coach? Heavens, no. The track coach should be judged based on multiple tests (track meets), and all testing should be counter-balanced by qualitative observations—team culture, enthusiasm, improvement, past performance, etc.

My father-in-law who worked for the Illinois Education Association once told me that teachers should be evaluated by multiple administrators, teachers, and students. I said, “But wouldn’t every evaluation be murky and meaningless?” He said, “Of course.” If he were still alive, he would be shocked to learn that teacher unions have succumbed to the notion that standardized test scores should factor into teacher evaluations.

![Six]()

All Men Are Not Created Equal

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Everyone loves the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, but I fundamentally disagree.

All biology teachers know that human life comes from the joining of sperm and egg, when 23 maternal chromosomes combine with 23 paternal chromosomes. The facts are the facts. Barring identical twins, no two humans are equal. Evolution produces diversity, not clones.

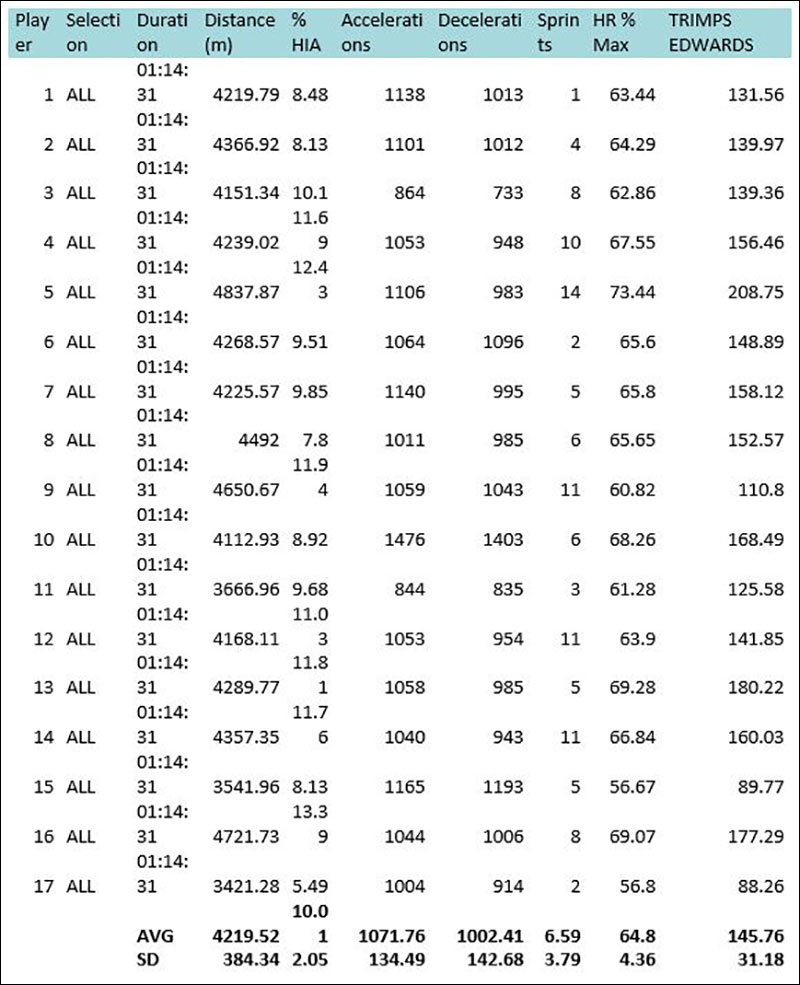

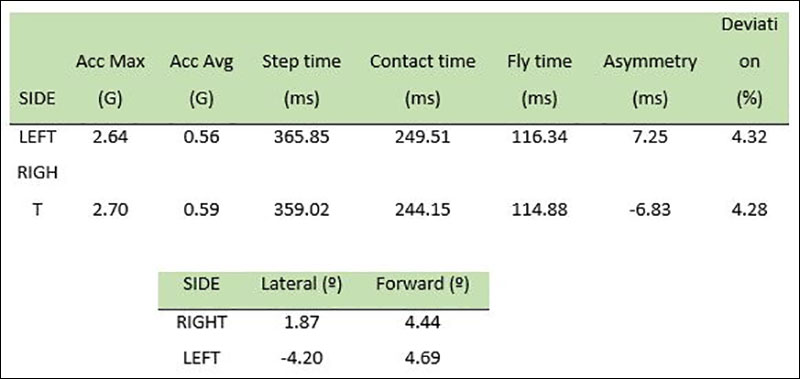

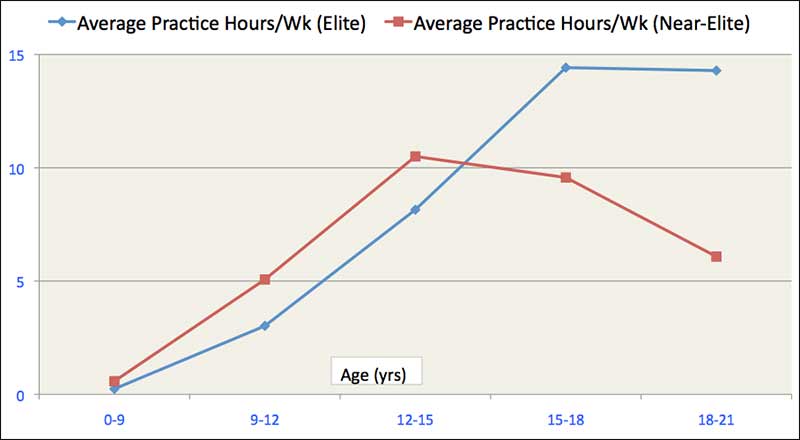

All coaches know, without a smidgeon of doubt, that athletes are not created equal. The opposite is true. My freshman football team spends the summer speed training. Check the rankings. The 40-yard dash is hand-timed, the 10-meter fly with Freelap Pro Coach. Forty-yard dash times range from 4.51 to 7.15, with ten-meter fly times from 1.02 to 1.84. My players range in size from 5-1 and 92 pounds to my starting left tackle at 6-0 and 235 pounds.

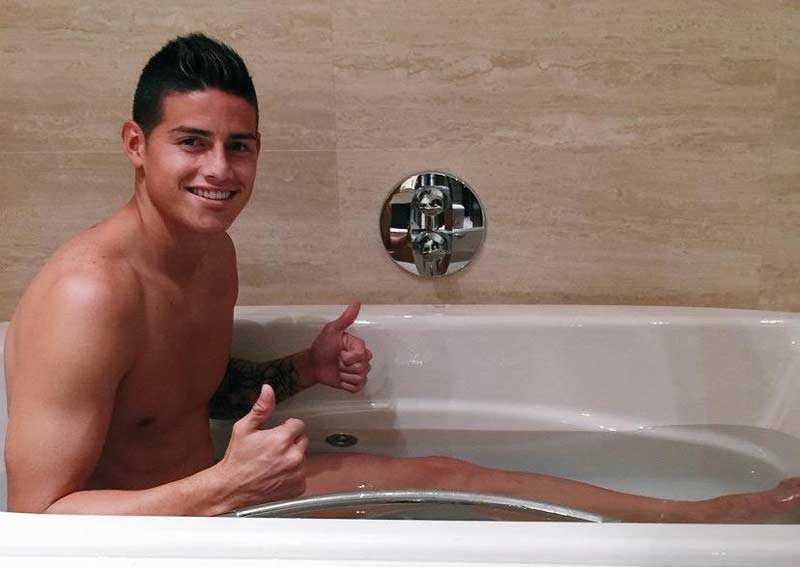

![Freshman Football Players]()

A freshman B game. Our running back weighs 80-some pounds. Our left tackle weighs more than four times that. Why are all kids expected to take the same classes and the same standardized tests? How can we celebrate diversity through standardized testing?

Track & field celebrates the differences in athletes. My track athletes seem like three different species of animal. My sprinters train like cats and act the same way. My distance runners remind me of well-trained dogs, hard-working and dependable. Throwers resemble grizzly bears—huge bodies capable of incredible feats of strength. My cats don’t throw the shot, my dogs don’t run the 100, and my grizzly bears don’t run the 2-mile. We are not created equal.

Birds all have wings but some fly, some swim, and some run fast. Birds would boycott standardized testing.

![Seven]()

Coaches Don’t Give Grades

Whenever grading is brought up in teachers’ meetings, the responses are predictable.

Some teachers think grading is the key to motivating students. Good students chase the “A” like it’s a carrot on a stick. Without grades, no one would try. Without grades, students are not held accountable.

Other teachers cling to zeros and failures with questionable zeal. These self-proclaimed old-school taskmasters hold punitive grading dear.

B.F. Skinner believed positive and negative reinforcement shape behavior. Grading is the reward and punishment in public education.

My theory: Teachers became teachers because they were good at playing the game of school. They followed the rules and stood in line. They kept their hands to themselves. They stayed in their seats and raised their hand before talking. School was fun. I can still remember taking my report card home and making my parents proud. I can still remember every book I read in sophomore English. Just because school worked for some, doesn’t mean it worked for all. Teachers cling to grades because they like grades.

Coaches don’t give grades. Coaches have no reason to reward with As or punish with Fs. I would argue that athletes, as a whole, are more motivated in sports than students in school. Chasing excellence is a powerful drug. Encouragement and recognition fuel the fire of competitive athletes. Report cards would not improve my football team. Track athletes compete with no fear of getting bad grades.

![Eight]()

Failure Is Not an Option

Too many kids fail courses in high school. I’ve seen teachers defend failure rates of 30%. If I were king, I would abolish “F” as a grade. If “D” means poor, how can you give a lower grade? In 35 years, I don’t remember failing anyone. The high school diploma is a certificate of attendance. Pass the kid.

Coaches have an advantage over teachers. Kids who skip practice or show insubordinate behavior are kicked off the team. On the other hand, public schools must educate everyone. Imagine teaching physics to a teenager who failed math and hates school. What’s the answer? First, don’t force kids who failed math to take physics. Second, failure is not an option.

Some freshman football players play like a deer in the headlights. I have kids who can’t tackle and shy away from contact— the athletic equivalent of trying to teach quantum mechanics to a kid without math skills. Some kids just don’t belong. Should I give unsuccessful football players an “F”? You coach kids of low talent by putting them in situations where they can succeed. 100-pound kids shouldn’t match up against 200-pounders. We always put kids in contact drills with others of similar size and ability. We play B-games after the A-game. Slower, smaller, and less-physical players find some degree of success. No one fails.

Track is a perfect sport. Slow guys run in slow heats. We measure every performance, so someone placing last in a race may still run a personal-record (PR) time. We celebrate the improvement of our lesser athletes more than our stars. Stars win races. Slow guys run PRs.

Soul-crushing teachers need to take a page from the coach’s handbook. Manufacture a way for kids to succeed. If they can’t hit a 95 mph fastball, put the ball on a tee and measure how far they hit it.

![Nine]()

Coaches Are Leaders, Not Bosses

“The difference between a boss and a leader: a boss says ‘GO!’ and a leader says ‘LET’S GO!’” – E. M. Kelly

Coaches are strong-willed decision makers. However, they know the secret to success is the team buy-in. No matter how smart the coach, his team must be committed to go in the same direction.

Head coaches must sell their ideas to their staff and teams. Militaristic generals don’t coach very long in modern high schools.

There’s not much “selling” going on in academia. The mandates are top-down. Administrators follow orders. Teachers follow orders. Students follow orders. Who gives these damn orders?

Bosses hire teachers who are “team players.” Administrators are often leery of independent, strong-willed, and assertive teaching candidates. Traits making a good coach sometimes disqualify would-be English teachers. In a new teacher orientation meeting ten years ago, I heard that teachers who “don’t play well with others” would not be around long. Just as ancient man domesticated sheep, teachers have been selected based on their willingness to be herded. No teacher I know likes data-driven education, Common Core, standardized testing, or teacher evaluation based on test scores. However, teachers have been well-trained to do their job and keep their opinions to themselves.

I probably wouldn’t last long as a principal. I would break too many rules and have too many opinions. However, I would hire some damn good teachers. In addition, the teachers in my building would own their classrooms. They would be independent, strong-willed, and assertive. I would empower my teachers, not domesticate them. Then I’d get fired.

![ten]()

Coaches don’t need advanced degrees

Huge organizations are slow to change and impossible to reform. As a wise drunk once told me about the Roman Catholic Church, “They should blow it all up and start over.” Whether the gin-soaked sage was right or wrong is debatable, but public schools should probably consider starting over.

We copied many educational ideas from Germany. Kindergarten (child-garden) is obviously German. So is the idea of advanced degrees. Somewhere, someone decided teachers’ pay should be based on two criteria: experience and advanced degrees. The postgraduate degree is also the prerequisite for becoming an administrator.

Ask a teacher if a postgraduate course ever made them better. The answer will usually be “No.” Postgraduate degrees involve a significant investment of time and money (usually a minimum of $15K), and the courses are crap. They are typically online. If you do have to show up for class, be ready for PowerPoint and someone paid by the hour to drone from a script. Coaches are hired based on their ability to coach. Coaches are judged on their ability to promote their program and establish a positive team culture. Teams with excited, enthusiastic kids are usually successful.

In education, postgraduate coursework is key. Our best young teachers can barely make car payments and have to split rent with a roommate. At the opposite end of the spectrum, an older teacher with a Ph.D. in something silly might make three times more. The principal at a nearby high school makes $174K. Several Illinois superintendents make over $300K. I find it ironic in education that the further you get from kids, the more you make.

A natural leader with great ideas will never lead a school unless he’s paid the tuition, taken the courses, and received his certification. Any teacher will tell you horror stories of educational leaders who had no business being in charge. They paid the tuition, took the courses, and received their certification. You can’t quantify teaching, and you can’t quantify leadership.

Coaches don’t increase their worth by taking meaningless courses. Coaches don’t jump through hoops to advance. How many Hall of Fame coaches had a Ph.D.?

Coaches are performance-based educators. Coaches “play to win the game,” and we need victories in education.

+++

Chris Korfist recently recommended Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder by Nicholas Taleb. Schools could benefit from disorder. I love Taleb’s statement, “If you see fraud and don’t say fraud, then you are a fraud.” Living paycheck to paycheck, most teachers don’t say fraud. We need to stop pretending. William Butler Yeats said, “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” Who disagrees with Yeats? Robotic teachers, mandated curricula, and standardized tests will never light a fire. FRAUD!!!

![Plainfield North Football Team]()

My 2012 freshmen team celebrating a 9-0 season after a cold and rainy final game. They played on a practice field with less than 100 people in attendance. Why can’t we light a similar fire in the classroom?

This article has harshly criticized public education. But don’t get me wrong. I love teaching. I could have retired last year, but I continue to teach. I’ve been a survivor, one of the lucky ones. My next article could easily be “The Miracle of Public Education,” praising schools.

Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire. — William Butler Yeats

In many ways, schools do a darn good job. High school graduation rates are closing in on 80%. High schools provide the best teenage day care ever invented. Students who take honors classes are well-equipped to study engineering, medicine, etc. The number of students attending U.S. colleges has tripled in the last 50 years. If kids have special needs, we modify their instruction, testing, and expectations. Schools have become surrogate homes to the homeless. We educate everyone in public schools.

Teaching is all I know. I’ve spent 39 of my 56 years going to high school and hanging out with teenagers. As I enter the twilight of my teaching career, I dream of better schools. I dream of independent students who are bold and assertive. I dream of students who have the enthusiasm of athletes. I dream of teachers who run their classrooms like football coaches, tailoring courses to the talents and interests of their students. Maybe it’s time to light a fire.

Please share so others may benefit.

Tony Holler

Tony Holler Chad Lakatos

Chad Lakatos

Alec Holler

Alec Holler

Lou Sponsel

Lou Sponsel Dan Hartman

Dan Hartman