By Eli Mizelman

Introduction

Bovine colostrum (BC) is the first milk secreted by cows after calving. Colostrum is high in protein and contains several bioactive substances including growth and antimicrobial factors (Donavan and Odle 1994; Reiter 1978). The main growth factor in BC is Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (Francis et al. 1988) which stimulates the growth of muscle tissue (Tomas 1991) and is important in maintaining muscle mass and function in adults (Borst 2001). Antimicrobial factors in bovine colostrum include immunoglobulin A (Mach and Pahud 1971) and a variety of other less specific antimicrobial proteins and peptides like lysozyme and lactoferrin (Korhonen 1977; Shing 2009) that are important for immune system function.

Previous studies have shown improvements in body composition (Antonio 2001), power (Buckley 2003; Hofman 2002) and strength (Duff 2014) when BC supplementation was taken during a resistance training program. The mechanism through which BC acts to benefit performance remains unclear.

The first study to investigate the effect of BC supplementation on exercise performance was Mero et al. in 1997. Since then, research has investigated the ability of BC supplementation to improve endurance, and anaerobic performance, and increase lean tissue mass, power, and strength. In addition, researchers are also trying to determine mechanisms for these improvements.

Body Composition and Strength

The first study to examine whether BC supplementation affects body composition and strength was published in 2001 (Antonio et al 2001). In the study, twenty-two trained males and females, were randomly assigned to either a BC (20 g/day) or a whey protein group prior to participating in an 8-week resistance and aerobic program that involved three training sessions per each week.

Body composition was analyzed before and on completion of the study using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Body mass significantly increased for the whey group, but primarily due to an increase in fat mass, while the BC group showed significant increase in lean body mass only, without any significant change in body weight. Strength was assessed at the same time points using 1RM strength tests. There was no significant difference between groups in strength.

However, another study (Kerksick 2001) found that upper body strength significantly increased after 12 weeks of resistant training and BC supplementation (60 g/day) in comparison to the same resistance training and placebo. Forty-nine trained males and females participated in the study and strength was determined by 1RM bench press and leg press. There was no significant difference for the leg press 1RM. In contrast to this finding, supplementation with the same dose (60 g/day) of BC, during eight weeks of strength and plyometric training, in fifty-one physically active males, was not associated with significant changes in strength (Buckley 2003).

In 2004, the effect of BC supplementation on changes in body composition was examined (Brinkworth 2004), using the same dose (60 g/day). In this study, active males trained the elbow flexors of their non-dominant arm four times a week. 1RM bicep curl, MRI and maximal voluntary isometric contraction of the upper arm were measured at baseline and after 4 and 8 weeks of supplementation. When compared with both their untrained arm and with the placebo group, upper limb circumference and total cross-sectional area were significantly increased in the trained arm of BC subjects. However, there were no significant differences between groups for upper limb muscle cross-sectional area.

Brinkworth et al. attributed the increase in the cross-sectional area following BC supplementation to an increase in skin cross-sectional area, based on a study that found that canine skin cells proliferate with increasing concentrations of BC (Torre 2006).

Duff et al. (2014) assessed forty older adults randomly assigned to 60g/day of BC or whey protein while participating in a three day/week resistance training program for eight weeks. Strength was assessed using 1RM bench press and leg press and body composition by DXA. BC supplemented participants increased their leg strength to a greater extent than whey protein supplemented participants. Bench press strength, on the other hand, as well as lean tissue mass, were not significantly different between groups.

Power

One of the first studies to investigate the effect of BC supplementation on power was conducted in a double-blind manner and a crossover design (Leppäluoto 2000). Ten athletes performed two jump tests on days 11 and 12 of the supplementation. After the overall analysis, it was found that BC supplementation significantly improved jump flight times in comparison to placebo supplementation. However, limited conclusions can be drawn from this study as neither the dose administered nor details of training and diet control was reported by the authors. The investigation is yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

In another double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study seventeen female and eighteen male elite field hockey players received either 60 g/day of BC or whey protein for eight weeks (Hofman 2002). Vertical jump performance improved more in the BC group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Buckley (2003) assessed 51 males who completed eight weeks of resistance and plyometric training while consuming 60 g/day of BC (n= 26) or whey (n =25). BC supplementation significantly improved peak cycle power and vertical jump height, suggesting that BC was beneficial to power activities.

Anaerobic Performance

Anaerobic glycolysis results in the production of H+ and lactate. Buffer capacity is the ability to bind free protons (i.e. to buffer H+), and offset reductions in pH during exercise; hence, given the strong association between acidosis and muscular fatigue, buffer capacity is an important attribute for maintaining anaerobic performance (Parkhouse 1984).

The main buffers of H+ come from skeletal muscle and include protein, inorganic phosphate, and phosphocreatine. Other components in blood including hemoglobin, bicarbonate, and plasma proteins also buffer H+. One study (Brinkworth 2002) examined whether BC supplementation could enhance the buffering of H+, in response to a 9-week training program with 13 elite female rowers who consumed 60 g/day of BC or whey. Two rowing tests were used to assess performance before and on completion of the supplementation period. Buffering capacity was estimated from the differences in the blood lactate levels and the blood pH levels that were taken at the end of each workload during the tests. It was found that buffering capacity was significantly increased after BC supplementation vs. placebo.

Brinkworth (2004) determined the component of blood buffering capacity that was enhanced following BC supplementation. There were no significant differences in hemoglobin levels, plasma bicarbonate levels or plasma buffering capacity in general between BC and placebo groups. The authors concluded that the observed increase in buffering capacity from their previous work (Brinkworth 2002) was the result of enhanced muscle buffering capacity, but they were unable to determine this because no muscle biopsy samples were collected.

Studies are mixed regarding the effect of BC on anaerobic performance. Hofman (2002) examined the effect of 8 weeks of BC supplementation (60 g/day) on sprint performance in 18 elite male and 17 female hockey players. Repeated sprint running performance (5 × 10 m) significantly improved in the BC supplemented group compared with the placebo group; however, only performance measures were reported in this study, so the mechanism behind the improvement in sprint performance is unclear. In contrast, Shing (2006) found no improvement in a time-to-fatigue test at 110% of ventilatory threshold, between BC and placebo in 29 highly trained male road cyclists. The dosage used in the study was only 10 g/day (for eight weeks); therefore, dosage may have been insufficient. Buckley (2003) used a higher dose of supplementation of 60 g/day of BC vs. whey for eight weeks on 51 males; however they also found that anaerobic work capacity was not different between the groups.

Bovine Colostrum supplementation significantly improved peak cycle power and vertical jump height.

Click To Tweet

Endurance

Shing (2009) studied 39 male subjects, supplemented with BC (60 g/day) or whey for eight weeks during an aerobic training program that included three 45-minute running sessions per week. The subjects performed two incremental treadmill tests, at baseline and at 4 and 8 weeks of supplementation. No significant changes in running performance were observed after four weeks, but, after eight weeks, subjects in the BC group covered a significantly greater distance and completed more work in the second treadmill test than the whey group. The mechanism for the significant improvement in running performance is unknown and also could not be explained by alterations in respiratory exchange ratio, lactate threshold or IGF-1 levels (Shing 2009).

Another study (Shing 2006) that used a dose of 10 g/day found that BC supplementation (in comparison to whey) improved 40 km time-trial performance at the end of a 5-day high-intensity training period but not during normal training. Although increased muscle glycogen levels during normal training do not improve endurance performance (Hawley 1997), during repeated days of high-intensity exercise, increased muscle glycogen levels may prevent and delay fatigue (Kavouras 2004; McInerney 2005). Due to these findings and the fact that colostrum feeding in calves is associated with enhanced activity of the rate-limiting enzymes for gluconeogenesis – pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Hammon 2003), BC supplementation may improve muscle glycogen resynthesis during periods of intense training.

Coombes (2002) assessed whether there was a dose response of BC on endurance performance. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 42 cyclists completed a work-based cycle time-trial (2.8 kJ/kg), following a 2-hour endurance ride, both before and after eight weeks of supplementation of 20 or 60 g/day of BC, or whey. Time-trial performance significantly improved in cyclists who were supplemented with BC (both dosages) when compared with the whey. The similar improvements in performance in both of the BC groups suggest that there may be a limit beyond which a higher BC dose does not provide any added performance benefit. The authors hypothesized that the improvement in the endurance was the result of enhanced nutrient uptake from the intestine, mediated by other growth factors found in colostrum. Nevertheless, the effects of BC supplementation on intestinal changes has not been directly measured yet.

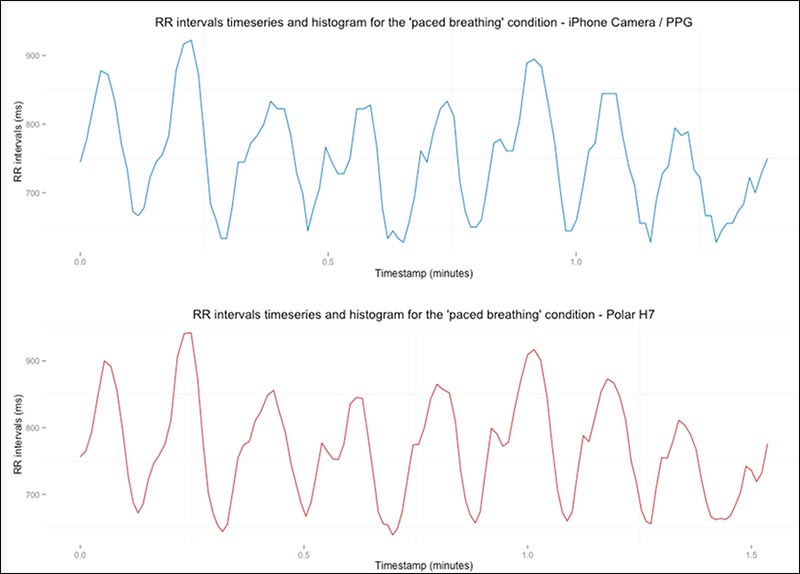

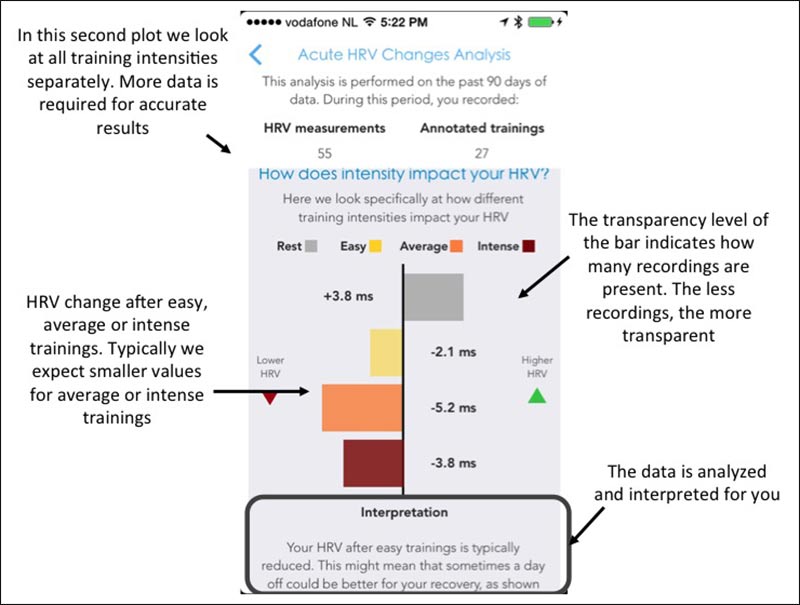

Shing (2013) assessed ten highly-trained male road cyclists randomly assigned to a 10 g/day supplementation of BC or whey, for eight weeks that ended in a five-day cycle race. BC supplementation significantly prevented a decrease in testosterone concentration over the race. In addition, parasympathetic indices of heart rate variability (i.e., increased RR intervals) were elevated in the BC group and reduced in the whey group, indicating better cardiovascular functioning with lower heart rate and higher cardiac output in the BC group.

Immune Function

Intense exercise suppresses immunity for several hours (Nieman 2000). Hence, athletes that perform high-intensity training are at a high risk for over-training syndrome (Halson 2002; Halson 2003; Mackinnon 2000) and upper respiratory tract infections (Mackinnon 2000; Fitzgerald 1991). Overtraining syndrome is a neuroendocrine disorder characterized by poor performance in competition, inability to maintain training loads, persistent fatigue, reduced catecholamine excretion, frequent illness, disturbed sleep and alterations in mood state. It is estimated that, at any given time, between 7 and 20% of all athletes may exhibit symptoms of overtraining syndrome. It is believed that excessively large volumes of training without adequate rest and recovery leads to overtraining syndrome (Mackinnon 2000).

The first study to examine the effect of BC supplementation on immune function (Mero 1997) reported that eight days of supplementation with a BC during normal training did not increase salivary IgA concentration. However, another study by the same authors (Mero 2002) showed that athletes ingesting BC for two weeks at a dose of 20 g/day experienced a 33% increase in salivary IgA concentrations. Note that in the second study, the duration of the supplementation was longer and the authors used BC powder that contains more immune factors than the liquid BC used in the first study.

In a study on marathon runners (Crooks 2006), a significant increase in salivary IgA levels was found after 12 weeks of 26 g/day BC supplementation in comparison to placebo; however, this was not associated with a difference in upper respiratory tract infections. On the other hand, two other studies (Shing 2007; Shing 2013) on male cyclists, with 10 g/day supplementation of BC for eight weeks, found no change in salivary IgA levels, natural killer cell cytotoxicity, lymphocyte or neutrophil surface markers. These results might be due to the lower dosage used in this study (10g/ day vs. 20-26g/ day).

Brinkworth (2003) investigated the relationship between BC supplementation and upper respiratory tract infections incidence based on several studies involving resistance training or endurance training interventions in which subjects ingested BC at 60g/ day vs. placebo, over an eight-week period. It was found that the percentage of participants that had upper respiratory tract infections was greater in the placebo group.

IGF-1

Note: “Colostrum is not prohibited by WADA, however, due to the fact that it contains certain quantities of IGF-1 and other growth factors which are prohibited, WADA does not recommend the ingestion of BC.” See WADA Prohibited List.

Despite the fact that BC contains IGF-1, only one group of authors reported significant increases in IGF-1 levels after BC supplementation for 8 and 14 days (Mero 1997; Mero 2002). IGF-1 is usually degraded in the gastrointestinal tract, but it was suggested that some factors in BC may improve the absorption of IGF-1 by preventing its breakdown (Playford 1993).

Normal IGF-1 levels for young adults are 14-48 nmol/L. The increase reported in the studies mentioned above, was approximately 5 nmol/L, while the amount of IGF-1 contained in the BC was 74 μg/day. At this dose, if 65% of IGF-1 was absorbed, the concentration of IGF-1 would only be expected to rise only by approximately 1.05 nmol/L. This suggests that the increase in serum IGF-1 was probably due to an increase in endogenous production (Shing 2009). Other studies with similar doses of BC and longer supplementation periods have reported no significant changes in IGF-1 levels following 4–8 weeks of BC supplementation (Buckley 2003; Coombes 2002).

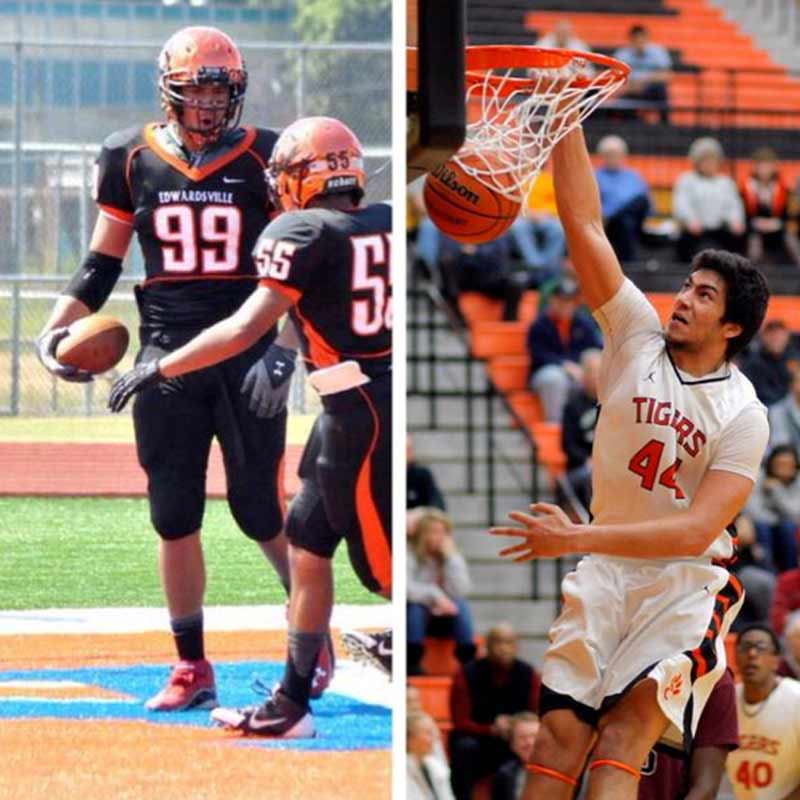

My Last Study

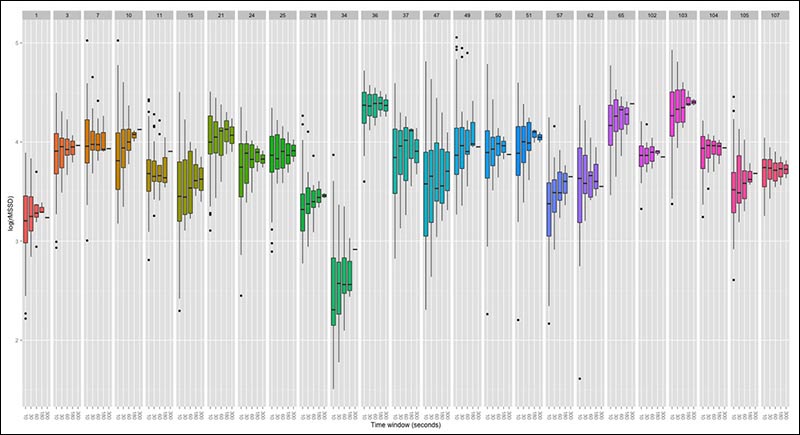

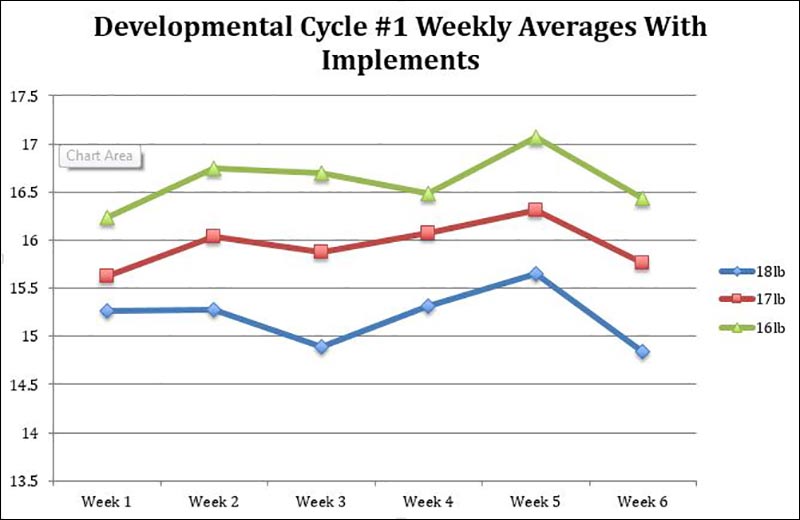

Last year, (study is yet to be published) we conducted a study that examined the effect of eight weeks of bovine colostrum supplementation in comparison to soy protein, on rugby players’: strength, power, anaerobic fitness, aerobic fitness, body composition, and IgA, IL-6, IL-1β and CRP levels, during the rugby season. In a double-blind manner and 1:1 allocation ratio, 29 players received 38g/day of protein from BC protein powder or soy protein. Both supplements were flavorless and had the same color, smell, and texture. We also controlled for energy intake and training regime for each athlete.

We found a significant difference in improving power (vertical jump) with the colostrum group increasing more than the soy group. We have also found a significant difference in improving aerobic fitness with the colostrum group increasing predicted aerobic capacity more than the soy group.

The author’s thematic poster from the 2015 ACSM Annual Meeting. The full-resolution poster can be viewed here.

Summary

Due to the small number of studies that have been conducted, we are far from having conclusive evidence for the improvement of performance by BC supplementation. Nevertheless, one can conclude from the mentioned studies that there is a great potential for BC to have a positive effect on athlete performance, especially when it comes to power, strength, and aerobic fitness.

Sport nutritionists should conduct more research on this matter so that 1) we will have sufficient statistical evidence to conclude whether BC does help improve performance, and 2) we would be able to hypothesis the mechanism in which BC acts in favor of improving athlete performance.

Please share so others may benefit.

References

- Antonio J, Sanders MS, Van Gammeren D. (2001). The effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on body composition and exercise performance in active men and women. Nutrition; 17: 243-7.

- Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Bourdon PC, et al. (2002). Oral bovine colostrum supplementation enhances buffer capacity but not rowing performance in elite female rowers. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab; 12: 349–65

- Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD. (2003). Concentrated bovine colostrum protein supplementation reduces the incidence of self-reported symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection in adult males. Eur J Nutr; 42: 228-32.

- Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD. (2004). Bovine colostrum supplementation does not affect plasma buffer capacity or hemoglobin content in elite female rowers. Eur J Appl Physiol; 91: 353–6

- Buckley JD, Abbott MJ, Brinkworth GD, et al. (2002). Bovine colostrum supplementation during endurance running training improves recovery, but not performance. J Sci Med Sport; 5: 65-79

- Buckley JD, Brinkworth GD, Abbott MJ. (2003). Effect of bovine colostrum on anaerobic exercise performance and plasma insulin-like growth factor I. J Sports Sci; 21: 577-88.

- Coombes JS, Conacher M, Austen SK, et al. (2002). Dose effects of oral bovine colostrum on physical work capacity in cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 34: 1184-8.

- Craig Twist and Jamie Highton. (2013). Monitoring fatigue and recovery in rugby league players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 8, 467-474.

- Crooks C, Wall C, Cross M, et al. (2006). The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation on salivary IgA in distance runners. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab; 16: 47-64.

- Duff W, Chilibeck PD, Rooke JJ, Kaviami M, Krentz JR, Haines DM. (2014). The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation in older adults during resistance training. IJSNEM; 24: 276 -285

- Fitzgerald L. (1991). Overtraining increases the susceptibility to infection. Int J Sports Med; 12 Suppl. 1: S5-8.

- Fry RW, Morton AR, Crawford GPM, Keast D. (1992). Cell numbers and in vitro responses of leukocytes and lymphocyte subpopulations following maximal exercise and interval training sessions of different intensities. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 64:218–27.

- Gabbett TJ. (2007). Science of rugby league football: A review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 23:9, 961-976.

- Gleeson M. (2005). Assessing immune function changes in exercise and diet intervention studies. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care; 8: 511-5.

- Halson SL, Bridge MW, Meeusen R, et al. (2002). Time course of performance changes and fatigue markers during intensified training in trained cyclists. J Appl Physiol; 93: 947-56.

- Halson SL, Lancaster GI, Jeukendrup AE, et al. (2003) .Immunological responses to overreaching in cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 35: 854-61.

- Hammon HM, Sauter SN, Reist M, et al. (2003).Dexamethasone and colostrum feeding affect hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes differently in neonatal calves. J Anim Sci; 81: 3095-106.

- Hawley JA, Palmer GS, Noakes TD. (1997). Effects of 3 days of carbohydrate supplementation on muscle glycogen content and utilization during a 1-h cycling performance. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol; 75: 407-12.

- Hofman Z, Smeets R, Verlaan G, et al. (2002). The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation on exercise performance in elite field hockey players. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab; 12: 461-9.

- Kavouras SA, Troup JP, Berning JR. (2004). The influence of low versus high carbohydrate diet on a 45-min strenuous cycling exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab; 14: 62-72.

- Kerksick C, Kreider R, Rasmussen C, et al. (2001). Effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on training adaptations II: performance [abstract]. FASEB J; 15: LB315

- Leppäluoto J, Rasi S, Martikkala V, et al. (2000). Bovine colostrum supplementation enhances physical performance on maximal exercise tests. 2000 Pre-Olympic Congress Sports Medicine and Physical Education International Congress on Sport Science; 2000 Sep 7–13: Brisbane (QLD).

- Mackinnon LT. (2000). Overtraining effects on immunity and performance in athletes. Immunology and Cell Biology; 78, 502–509.

- McInerney P, Lessard SJ, Burke LM, et al. (2005). Failure to repeatedly supercompensate muscle glycogen stores in highly trained men. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 37: 404-11.

- Mero A, Kahkonen J, Nykanen T, et al. (2002). IGF-I, IgA, and IgG responses to bovine colostrum supplementation during training. J Appl Physiol; 93: 732-9.

- Mero A, Miikkulainen H, Riski J, et al. (1997). Effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on serum IGF-I, IgG, hormone, and saliva IgA during training. J Appl Physiol; 83: 1144–51

- Mero A, Nykänen T, Rasi S, et al. (2002). IGF-1, IGFBP-3, growth hormone and testosterone in male and female athletes during bovine colostrum supplementation. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 35: s299

- Nieman DC. (2002). Is infection risk linked to exercise workload? Med Sci Sports Exerc; 32: S406-11.

- Parkhouse, W.S., and D.C. McKenzie. (1984). Possible contribution of skeletal muscle buffers to enhanced anaerobic performance: a brief review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 16:328-338.

- Playford RJ, Woodman AC, Clark P, et al. (1993). Effect of luminal growth factor preservation on intestinal growth. Lancet; 341: 843–8

- Rhind SG, Shek PN, Shinkai S, Shephard RJ. (1994). Differential expression of interleukin-2 receptor alpha and beta chains in relation to natural killer cell subsets and aerobic fitness. Int. J.Sports Med.15: 911–18.

- Shing CM, Hunter DC, Stevenson LM. (2009). Bovine colostrum supplementation and exercise performance: potential mechanisms. Sports Med; 39: 1033–1054.

- Shing CM, Jenkins DG, Stevenson L, et al. (2006). The influence of bovine colostrum supplementation on exercise performance in highly-trained cyclists. Br J Sports Med; 40: 797-801.

- Shing CM, Peake J, Suzuki K, et al. (2007) Effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on immune variables in highly trained cyclists. J Appl Physiol; 102: 1113-22.

- Shing CM, Peake JM, Suzuki K, Jenkins DG, Coombes JS. (2013). A pilot study: bovine colostrum supplementation and hormonal and autonomic responses to competitive cycling. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness; 53(5): 490-501.

- Smith LL. (2004). Tissue trauma: the underlying cause of overtraining syndrome? J Strength Cond Res. 18(1):185-93.

- Torre C, Jeusette I, Serra M, et al. (2006). Bovine colostrum increases proliferation of canine skin fibroblasts. J Nutr; 136: 2058–60

- Urhausen A, Gabriel H, Kindermann W. (1995). Blood hormones as markers of training stress and overtraining. Sports Med. 20: 251–76.

- O’Gorman D, Hunter A, McDonnacha C. (2000). Validity of field tests for evaluating endurance capacity in competitive and international-level sports participants. J Strength Cond Res. 14 (1): 62-7.

- Duthie G, Pyne D, Hooper S. (2003). Applied physiology and game analysis of rugby union. Sports Med. 33 (13): 973-991.

- Woof JM, Ken MA. (2006). The function of immunoglobulin A in immunity. J Pathol. 208: 270–282.

- Ingle PV, Patel DM. (2011). C- Reactive protein in various disease condition- an overview. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 4(1): 9-13.

- Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Fischer C, Keller C, Keller P, Plomgaard P, Wolsk-Petersen E, Febbraio M. (2004). The metabolic role of IL-6 produced during exercise: is IL-6 an exercise factor? Proc Nutr Soc. 63, 263–267.

- Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Asp S, Schjerling P, Klarlund Pederse B. (1999). Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance in strenuous exercise in humans. J Physiol. 515.1, 287—291.

The post Effect of Bovine Colostrum Supplementation on Athlete Performance appeared first on Freelap USA.