![Female High Jumper]()

By Joel Smith

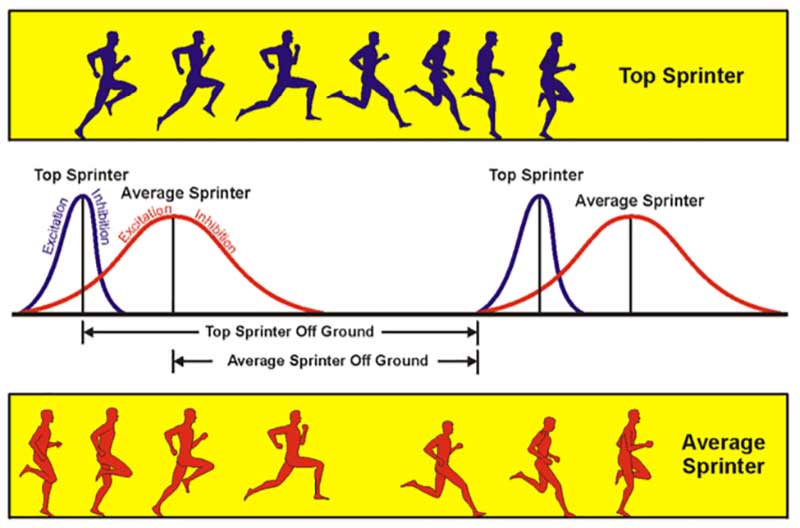

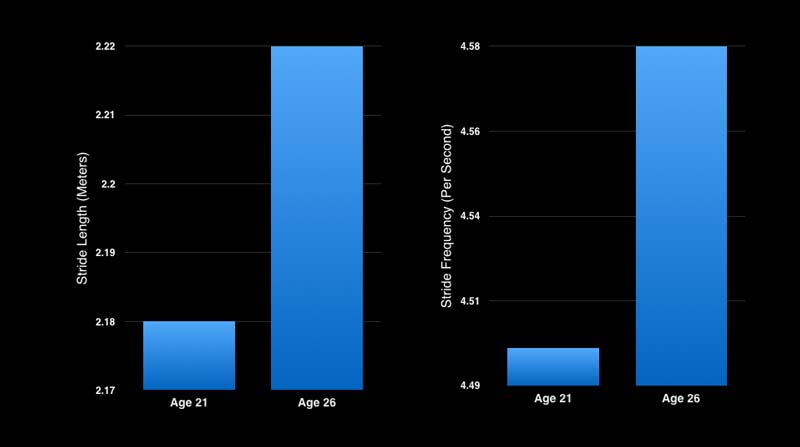

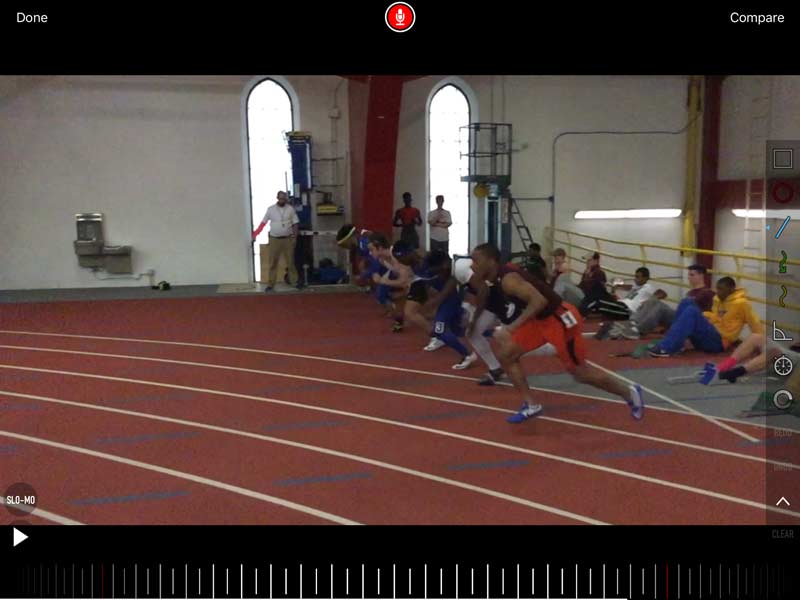

When Donald Thomas waltzed off a basketball court in 2006 into his first track meet, with only one high jump practice under his belt, he shocked the nation by high jumping 2.22m (7’3”) wearing Nike Shox basketball shoes. The highest jumpers in the world come from basketball and volleyball courts, but most coaches don’t consider the scientific and motor learning reasons behind this phenomenon.

Video 1. Donald Thomas clears 2.22m in Nike Shox after one high jump practice.

I love anecdotes from the world of slam-dunk specialists largely because many coaches who are well versed in structured regiments and periodization schemes would laugh at the “training” in this hoops subculture. And yet social media is becoming more and more buzzed with gravity defying exploits of street dunkers. Many of these athletes haven’t touched a weight, heard a single cue from an experienced coach, or read a word about how to plan training.

How do these athletes manage such ridiculous jumps? Here are some hints. First, they are highly motivated and have a passion for jumping. Distinguished USSR high jump coach Victor Lonsky described this as “an itch in the soles of the feet.” Second, when they jump, they don’t just dunk on a 10-foot rim the exact same way each time. They twist, they spin, they might do cartwheels and back handsprings, and they have a lot of fun. All of these jumps yield different plant rhythms and sequences as well as outcome goals. Here are two of my favorite videos highlighting these ideas.

Video 2. Justin Darlington doesn’t lift weights or have a “training program,” but he can do this.

Video 3. Here is another great athletic dunk.

To help vertical jump athletes reach their highest potential, a variety of specific strength, power, and coordinative training is essential to maximize performance gains. There is an important aspect of motor learning that has a massive impact on the way we understand programming and athletic adaptation to training as we know it.

This aspect encompasses the subtle, and not so subtle, variations of key athletic movements, in this case jumping, that allow athletes to respond better to training over a period of time and acquire a higher performance level. With this in mind, we’ll jump into the idea I call specific power variability.

Specific Power Variability

Doing the exact same jump over and over, without adequate variation, is the “silencer” of vertical gains. This concept isn’t only true in athletic performance but also life in general. Nature itself is a balance between order and chaos. Without some level of chaos, or randomness, life ceases to exist.

I recently read Frans Bosch’s latest book on strength training and coordination, Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach. Bosch states that movement must have degrees of freedom to promote learning and progression. In other words, there must be some level of chaos, or room for the CNS to self-organize movement, to reach a goal. When exercises offer no degrees of freedom (such as a heavy barbell lunge), the athlete’s CNS is in a “straightjacket,” and no motor learning is possible.

John Keily describes training a skill as a trek through a densely undergrown path. The more you train the skill, the more you narrow the path, making it harder to keep walking along it. The more variable you train that skill, the wider you keep the path. The wider the path, the more easily you can move through it, but if it becomes too narrow, continued progress is difficult. Hence, a certain level of variability is vital to continue to make training progress and stay injury free.

As coaches, we are guides to the athletes’ subconscious systems. The athletes cannot consciously control how their brains shuffle through the adaptive systems of training nor can coaches control the exact way in which their nervous systems process stimuli and the exact mechanical manifestations from that process. The best we can do is to put an athlete in an environment that helps to promote the way we want them to adapt.

Applying Variability

In this article, I talk about four types of variability coaches can use to guide a jump athlete’s speed, power, and technical ability down the correct path. These are listed in order of their use, from beginner through advanced athletes. The beginning of the list is more useful for beginners while the end has more application for advanced trainees. This isn’t to say that beginners can’t benefit from #4 or advanced athletes can’t improve with #1 or #2; these are general guidelines. Four ways to induce specific power variability into jump training are:

- Complex training

- Fatigue induced learning

- Same but Different

- Induced randomness/chaos

![One]()

Complex Training

Vertical jump training can become more robust through variability with both a mixed attempt format and the compounded effect exercises have on each other in a complex format.

Complex training is largely applicable to the widest spectrum of athletes in respect to potentiation. Dr. Bondarchuk has said, “In the future, in the track and field speed-strength events, we will see the complex method of constructing separate training sessions.” I was fortunate to hear Dr. B talk about complex methods in the weight room for advanced athletes at the 2014 Central Virginia Sports Performance Seminar, and potentiation exercises were a big part of his lecture. From a purely motor learning perspective, complex training is most applicable to beginners, but potentiation is useful for all levels.

Unfortunately, most coaches think of complex training only in terms of potentiation and, although this is an important aspect of stringing together a series of jumping, lifting, and throwing exercises, it is critical to also look at a series of exercises as a motor learning tool. Performing an exercise directly before another influences the mechanics of the second exercise in either a coordinative or fatiguing manner. For now, I’ll talk about the coordination aspects and cover fatigue in the next section.

Looking at the coordination effects of complex training, strength coach legend Dan John has some wonderful, insightful training methods using a kettlebell in the throwing ring. He uses various kettlebell drills, such as swings, goblet squats, single arm presses, and snatches, to settle his body into the rhythm he is trying to accomplish technically in the throws. He calls this “reflexive training”; using an exercise to “trick” an athlete into acquiring the desired body position while sparing willpower.

By alternating kettlebell work and throwing, Dan creates a powerful motor stimulus that teaches technique without spending an athlete’s mental forebrain energy on each throw, enhancing the workout and retention of technique. Complex training teaches motor patterns more effectively than simply potentiating prime movers haphazardly.

To this end, we must look at every movement complex from not only a potentiation standpoint but also a coordinative one. Better than simply aiming for gross potentiation, such as performing a heavy back squat followed by a vertical jump, it is much more useful to build complexes where specific skills are targeted, potentiated, and repeated. On simple terms, we can utilize movements like basic barbell lifts, medicine ball throws, and depth jumps to provide a coordinative transfer to subsequent jump attempts. French Contrast is one of the best ways to do this. A French Contrast circuit utilizes two strength exercises and two speed exercises in alternating circuit fashion.

A good coach can steer the nature of the French Contrast towards the specific technical output desired. The French Contrast’s total effect is not just potentiation but also a heavy coordination boost. In the video below, specific skills from a two-foot vertical jump are trained in a French Contrast format. Regarding what the coaching world has found to improve an athlete’s coordination and power in vertical jumping, the French Contrast offers one of the best training layouts.

Complex training concepts are important for motor learning in track and field jumpers. Alternating a drill such as the box takeoff below with actual long jump takeoffs is a useful method to “trick” an athlete into the proper takeoff rhythm, similar to Dan John’s kettlebell work for the throws. Once the rhythm is established, it becomes ingrained in the nervous system for future efforts.

Video 4. Long jump technique.

In my time working with swim athletes, I’ve learned that swim coaches use lots of variation through fins, paddles, socks, chutes, and simply heavy kick cues, to create the motor change they want to accomplish in the water. These movements are often complexed to create a better technical response. Track coaches can often get away with leaving technique alone in simple blocked training patterns because running is more instinctive, and thus less trainable, than swimming, but they can certainly learn from the motor learning ideals of aquatics and create faster sprinters and higher jumpers in the process.

![Two]()

The Role of Fatigue in Variability

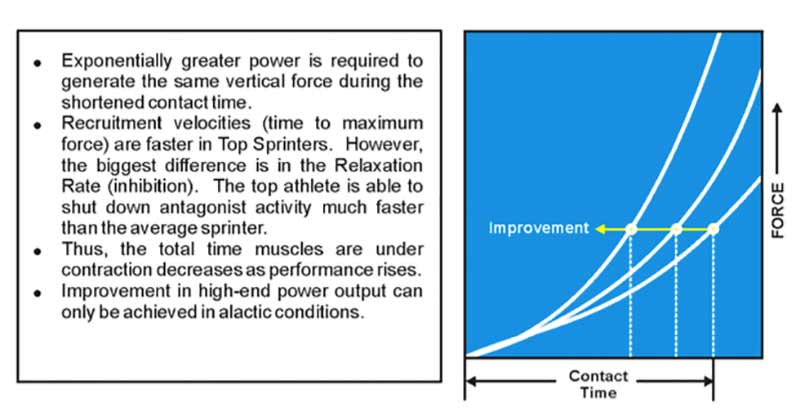

In Strength Training and Coordination, Bosch mentions that fatigue can play an important role when building better motor patterns in sport. As speed and power coaches, we often look at anything fatigue-inducing with disdain, saying “look how technique fell off.” Bosch teaches us that fatigue causes the body to formulate a new recruitment pattern to deal with the building level of muscle fatigue. Clearly, this is only beneficial to a point. Fatigue is useful only as long as technique remains somewhat close to optimal.

When muscle fatigue rises, the body relies more on elastic elements to continue designated movement patterns. An example would be performing a set of squats and then immediately performing a round of eight consecutive hurdle hops. The muscle fatigue (contractile elements) from the squats force the body to formulate a greater contribution of elastic elements in the hurdle hops, which magnifies the purpose of the hurdle hops.

Some time ago, my college jumps coach was in contact with a Russian jumps coach, Egor. My coach received all sorts of interesting information which he shared and implemented with me. I hung on to every word and found the training advice more than helpful. As a coach, I used his advice on distance flops and scissors over a low bar with great success.

In my later coaching years, I contacted Egor and learned an interesting practice where you place the high jump bar to 6’-6’4” and jump it 50 times with a full approach, jogging back to the start mark after each landing.

This sounds crazy, but this type of practice is more common than you may think and, as we have just seen, has a plausible motor learning rationale. The two-minute drill, used by triple jumpers such as Christian Taylor, involves the following sequence: perform a triple jump from a short approach, about five strides; jog back to the starting mark, and repeat. Perform this for two minutes, trying to maintain technique under fatigue.

We tend to get stuck thinking that only maximal efforts count toward building competition technique, but a small percentage of training effort can be used to use fatigue when building a better motor program in the jump. Fatiguing efforts in jumping offer a unique motor stimulus that improves the interaction of muscle and tendon in conjunction with maintaining an athlete’s optimal jump technique.

Again, this tactic is only effective within reason. I don’t believe in regularly allowing athletes to sprint or jump with poor technique. Fatigue training generally bodes well as a finisher of typical workloads that are done with relatively good momentary technical accuracy.

When applying French Contrast work, we can assume that the relatively short rest breaks between exercises in French Contrast yield small fatigue elements that may force the body to increase elastic contribution in the workout’s speed-strength elements.

![Three]()

Same but Different

I first learned of the Same but Different idea while reading the book, Easy Strength by Dan John and Pavel Tsatsouline. Suddenly many ideas in the world of training made sense.

In Supertraining, Siff and Verkhoshansky state, “The competitive action executed with maximal physical exertion represents the most specific of all the special training means.” Athletes have only a certain amount of stored energy when it comes to maximal efforts in their primary directive. This idea represents much of what is utilized in the “Westside” powerlifting program, where the competitive lifts are sparsely addressed in their intense and competitive state, and large amounts of lift variations performed with high intent are prescribed during the rest of the training week.

The essence of Same but Different retains specificity under new biomechanical, environmental, and psychological constraints. The psychological constraints may be the most underrated and often are not considered when creating training variation. Basic examples from the weightlifting world are alternating a sixteen-week powerlifting program with three or four weeks of bodybuilding training or going from a competition low-bar squat to a few weeks of high rep high bar Olympic squats. A swimmer might take two or three weeks after the end of the season to play water polo, and so on.

Within the scope of jumping, complicated and environmentally different versions of movement offer a gold mine of options for helping the nervous system to form a better training pattern over time. Continually training the same exact skill and motor enneagram doesn’t give an athlete’s nervous system room to create improvement and leads to burnout. Training a skill properly requires a very high volume of specific training, but with an activity as physiologically demanding as jumping, it is very important that much of this specific training be performed under subtly different biomechanical and emotional constraints.

In Easy Strength, Tsatsouline shares a Vladimir Issurin (Block Periodization) anecdote about a coach who decided to get rid of all general exercises and make the preparation of his athletes exclusively sport specific. Many months later, none of the athletes had set a PR and many had regressed in performance. So much for the sport-specific approach to training that is so overbearing in our private sector sport-performance culture.

In the high jump world, high school basketball players make up a huge portion of the talent pool. There are loads of high school stories regarding jumpers coming straight off the basketball court clearing personal best heights and then floundering to sub-par jumping as they move away from basketball and start an extensive amount of specific high jump training and heavy weightlifting. In these scenarios, the specific high jump training is too monochromatic, and the heavy weightlifting is poorly designed, and the two combine to “straightjacket” the nervous system. The result: lousy jumps that the coach blames on the athlete’s lack of focus.

Back in my NCAA DIII coaching days, I saw college basketball players waltz off the basketball court in late February and win NCAA indoor national track meets in the high jump, who then stagnated in the outdoor campaign once they began to train specifically. Wouldn’t the specific high jump training in the outdoor campaign help their high jump technique and precision jumping ability? Not as much as we might think.

Athletes in weaker physical states will benefit from training that resembles a higher order of chaos to broaden the path of their nervous systems. Sometimes the best thing you can tell a jumper who is weary from the wear and tear of depth jumps, bounds, sprints, throws, and hops, is to simply go play soccer or ultimate Frisbee for a few days to help widen their path. Just hope they don’t twist an ankle.

In 2000, Matt Hemingway, who had walked away from high jumping two years earlier, found redemption through slam dunking during pickup games at work. His dunking exploits fueled his return to high jump, and his 2000 result of 2.38 was a PR and the highest jump Americans had seen in some time.

This type of story epitomizes Same but Different.

Here are a few practical examples for jumpers.

Video 5. Stefan Holm and 6 Degrees of Jumping

I love, and regularly make use of, these jump variations with my youth high jumpers. Even with collegiate and elite level athletes, practicing more than one style can yield solid benefits. I think it’s accurate to say that this type of work helped Holm with his career.

Video 6. Stephan Holm Hurdles Training.

Holm hurdles are another great way to train jumping under different environmental constraints while building takeoff rhythm. For complicated jumping patterns, I enjoy using hurdles. They force a higher rate of power development in a shorter time frame and provide agility that helps athletes to continually develop well-rounded athletic performance.

Video 7. Low-Rim Dunking.

This is an example of jumping with a dunker who is pretty famous now. Did you see his dunk in jeans at halftime of the NBA All-Star game? Many internet sensation slam-dunkers do a good amount of work on lower rims and many will tell you that it builds their jumping height. In reality, low-rim dunks likely offer a mental break from typical 10-foot rims and allows more focus on some of the fluctuators in common jump movements. This gives the CNS continual puzzles to solve and keeps the width of the path at an appropriate level.

![Four]()

Induced Randomness (Chaos)

An athlete must train specifically to improve vertical jumps, but that specificity can become more effective with an element of induced randomness. Induced randomness is a sound method of adding variability into a more specific skill path and works by making a movement subtly different while maintaining most other competitive constraints. In other words, you give an athlete a small error in the movement to provide the nervous system a chance to correct it. It has been postulated that motor learning is actually more about fixing errors than perfecting technique.

As far as track and field go, one way to implement induced randomness is to have athletes pulled in an overspeed setting and, while in route, attempt to stride on a few small pieces of track laid out on their course. I learned of this idea from Chris Korfist, who is doing some great things with the 1080 sprint trainer.

Other coaches have their athletes sprint onto irregularly spaced chalk or tape marks during their sprints. This plays with the rhythm of the movement and creates an error to be organized by the nervous system. Athletes must solve, on the fly, movement puzzles which optimize their technique on the fastest and most specific level.

Induced randomness training, however, isn’t completely new. Twenty years ago, Polish jumps coach Tadeusz Starzynski sent jump athletes on 200m repeats over uneven terrain as a means of general preparation. Distance coaches in the past have had athletes run on different terrains such as rocky trails and sand dunes. This also falls under the realm of Same but Different. Some forward-thinking coaches have intuitively understood these concepts for some time, but the methods are now coming full circle with more purpose, intent, and intensity.

There is a famous study of long jumpers conducted by Rewzon which appeared in Science of Sports Training by Thomas Kurz. In this study, long jumpers performed one of two training programs.

- Program One was simply to practice long jumping and “jump as far as you can each jump” in every training attempt.

- Program Two was “jump a different distance with each jump, and be accurate with the landing.”

The Program Two athletes, who jumped different distances, were able to best their max-only counterparts when it came time to jump all-out for distance at the end of the training study. These jumpers, who fed their nervous system more randomness, created a more robust overall system for the one important big jump attempt. Giving the CNS more possibilities of movement allows the creation of a better program compared to providing only one possibility.

Looking back at the example of high-level slam-dunk athletes, the induced randomness of dunk training is perfect for vertical jump athletes who already have high skill levels. At the higher performance levels, athletes are stable in the fundamental points (attractors) of their jump technique, and rightly so. At this point, complex training for skill acquisition is less important than fine-tuning existing qualities. The same principles will ring true for high-level sprinters and jumpers. They will benefit more from solving a motor puzzle via induced randomness within their event type than performing a series of fundamentally different jumps or sprints to improve technique.

Below are some examples of using induced randomness/chaos with jumpers.

For High Jump:

I enjoy the Swedish technique for training jumpers, and Stefan Holm’s various training schemes are no exception. I particularly like his high jump run-up drills, as they include elements of fatigue, rhythm, and randomness, but are all high velocity and specific enough to apply to all levels of jumpers. In this video, Holm does a run-up with a random single leg bound leading into the penultimate series.

Video 8. Stephan Holm’s High Jump.

Holm also performs a version of this drill with a long series of single leg bounds leading into his penultimate takeoff series. The long series drives an even greater rhythm and fatigue element which leads to a strong, unique motor learning effect in the takeoff.

For Triple Jump and General Posterior Chain Power:

Variable bounding is a simple and extremely effective way to induce subtle randomness into an explosive sequence. This type of bounding, where cones are set at intervals up to 20% difference on each stride, also causes a more “reflexive” feeling from the athlete in many cases.

Video 9. Joel Smith Variable Bounding

Final Summary and Training Suggestions

To help coaches and jumpers build a more effective total program, I’ve included a master list of ways to apply the four forms of variability. Remember, these methods should not compromise the entire program, but should comprise enough of a portion to ensure that the motor pattern of and athlete is continually fresh and improving. For some athletes, this might mean 10-20% of the program is based on some form of variability. For other athletes, at least 50% of the program might revolve around a chaotic and complex system. Different athletes have different needs for training variation.

- A variety of high jump takeoffs, not just the flop style (straddle, scissors, western roll, head on hurdling, various clearances off of two feet)

- A variety of long jump takeoffs over hurdles or barriers or with various small box constraints around the penultimate steps

- Hurdling movements and jumps

- Bounding combinations

- Variable bounding

- Parcour style jumps, that can be performed safely, or safe recreations of parcour style jumps

- Run, or at least practice, the hurdle events

- Slam dunks as well as creative low-rim slam dunks

- Play basketball or volleyball, at least as a shakeout or cooldown

- Complex lifting and jumping exercises

- French Contrast training

- Complexing bounding with jumping

- Complexing depth jumping with specific jumping

Variability can also be used in a practical, rotating manner on the workout-to-workout level. I make use of this format in my book, Vertical Ignition, which has yielded some great vertical gains, particularly in track and field athletes.

When it comes to vertical jumping, particularly skilled versions such as running jumps in track and field, training variation and coordination is a critical aspect of improvement. Funneling all training into rigid buckets can have drawbacks. Sprinting, jumping, and all movements in between, can and do work synergistically to create a stronger jumping technique.

Please share so others may benefit.